Contrary to the popular belief that Pharaohs were always male, there were a number of great female Pharaohs of Egypt and for the most part, their reigns were successful, peaceful and prosperous. Living in a world dominated by men, the powerful women who ruled Ancient Egypt were unusual and extraordinary woman and leaders of their time. Rulers such as Cleopatra VII, Philapator, Twosret, Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, Sobekneferu and MerNeith were among the few women of antiquity to reign during Egypt’s long history.

Hatshepsut – Image Source: American Research Center in Egypt

Hatshepsut is one of the more intriguing figures among these powerful Egyptian women rulers. She was also one of the longest reigning female Pharaoh (22 Years). Her Reign was established between c. 1478-1458 B.C. (18th Dynasty) and she is the second historically confirmed female pharaoh. At the age of 12, Hatshepsut became the queen of Egypt, due to marrying her half-brother Thutmose II, and then acted as royal regent to her infant stepson, Thutmose III, after Thutmose II died.

Less than seven years into her time as regent, Hatshepsut assumed the title of Pharaoh, with the full power and authority thereof. Officially, for political purposes, she continued to rule jointly with Thutmose III, but it was clear that she was fully in charge. In order to legitimize her power grab, Hatshepsut ordered that all official representations of her were to depict the traditional regalia and accepted symbols of Pharaoh, such as the ‘Khat’ headcloth topped with the ‘uraeus’, the ‘false beard’ and the ‘shendyt’ kilt. Thutmose III later tried to erase this depiction of Hatshepsut from Egyptian history following her death, which is why the many statues of her that remain alternatively use elements of traditional female iconography as well as the male regalia.

Hatshepsut’s Achievements:

During her reign, lasting over two decades, Hatshepsut expanded Egypt’s trade routes as well as undertaking some ambitious and historically significant building projects. Due to this massive building program, she became one of the most prolific builders among all of the Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt.

She repaired the damage to the Empire caused by the Hyksos by re-establishing trade networks that had not fully recovered from the expulsion of the Hyksos at the end of the second intermediate period.

Traditionally, Egyptian kings defended their land against various enemies who threatened Egypt’s borders. Hatshepsut formed a foreign policy based primarily on trade, rather than being directed by war and conflict. In Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple there are wall scenes depicting a short but very successful military campaign to Nubia.

Also recorded in Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, her voyage to punt is regarded as her most successful military campaign. It resulted in the return of precious gems, incense, trees, animals and many other luxuries of the era. Some evidence shows that she also led campaigns in the Levant and Syria. (J. Hill, 2010)

Hatshepsut also established a trading center on the East African coast, beyond the southernmost part of the Red Sea from which goods like gold, ebony, animal skins, processed myrrh, baboons and livings myrrh trees were transported back to Egypt.

A number of magnificent temples and structures were rebuilt by Hatshepsut. Early during her reign, she commissioned the great temple at Deir el-Bahri, believed to be her most impressive architectural achievement. Among her many other restorations and projects was the renovation of her father’s great hall in the temple of Karnak.

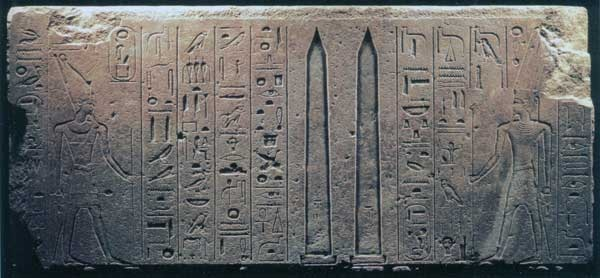

Hatshepsut also built four great obelisks that reached 30m high. Two of these obelisks were built outside the restored temple of Mut. At the time they were erected, they were the tallest standing obelisks in the world (I. Shaw, 2003).

In 1458BC: Hatshepsut died of unknown causes. At the end of her life, she was laid to rest in the Valley of the Kings. Since her death, many of her names and achievements were partially removed. This is why she was not recognized until the 1860s when Hatshepsut’s temple was discovered with most of the remaining records of her reign still located inside.

Statue of Hatshepsut as a male Pharaoh at the Temple of Deir el-Bahari.

Image Source: http://www.safariegypt.com/Information/important_topics/queen_hatshepsut/photos/hatshepsut_head.JPG

References:

Hill, J., 2011. Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt: Cleopatra VII – character. [online] Ancient Egypt Online. Available at: http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/Cleopatra-character.html

Shaw, I., 2003. Exploring ancient Egypt. 1st ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

~ Dean Winwood